🔎

Skalarprodukt 💡

Das Skalarprodukt zwischen a ⃗ = ( a 1 a 2 a 3 ) \vec a = \left(\begin{smallmatrix}

a_1\\a_2\\a_3

\end{smallmatrix}\right) a = ( a 1 a 2 a 3 ) b ⃗ = ( b 1 b 2 b 3 ) \vec b = \left(\begin{smallmatrix}

b_1\\b_2\\b_3

\end{smallmatrix}\right) b = ( b 1 b 2 b 3 )

a ⃗ ∘ b ⃗ = a 1 ⋅ b 1 + a 2 ⋅ b 2 + a 3 ⋅ b 3 \vec a \circ \vec b =

a_1 \cdot b_1 +

a_2 \cdot b_2 +

a_3 \cdot b_3 a ∘ b = a 1 ⋅ b 1 + a 2 ⋅ b 2 + a 3 ⋅ b 3 Satz 💡

Zwei Vektoren a ⃗ ≠ o ⃗ \vec a \neq \vec o a = o b ⃗ ≠ o ⃗ \vec b \neq \vec o b = o senkrecht zueinander, wenn

a ⃗ ∘ b ⃗ = 0 \vec a \circ \vec b = 0 a ∘ b = 0 Rechenregeln 💡

a ⃗ ∘ b ⃗ = b ⃗ ∘ a ⃗ r ⋅ a ⃗ ∘ b ⃗ = ( r ⋅ a ⃗ ) ∘ b ⃗ = a ⃗ ∘ ( r ⋅ b ⃗ ) ( a ⃗ + b ⃗ ) ∘ c ⃗ = a ⃗ ∘ c ⃗ + b ⃗ ∘ c ⃗ a ⃗ ∘ a ⃗ = ∣ a ⃗ ∣ 2 ≥ 0 \begin{align}

\vec a \circ \vec b &=

\vec b \circ \vec a

\\

r \cdot \vec a \circ \vec b &=

(r \cdot \vec a) \circ \vec b =

\vec a \circ ( r \cdot \vec b)

\\

(\vec a + \vec b) \circ \vec c &=

\vec a \circ \vec c + \vec b \circ \vec c

\\

\vec a \circ \vec a &=

|\vec a|^2 \geq 0

\end{align} a ∘ b r ⋅ a ∘ b ( a + b ) ∘ c a ∘ a = b ∘ a = ( r ⋅ a ) ∘ b = a ∘ ( r ⋅ b ) = a ∘ c + b ∘ c = ∣ a ∣ 2 ≥ 0 Beispiele ( − 2 0 2 ) ∘ ( 1 2 4 ) = − 2 ⋅ 1 + 0 ⋅ 2 + 2 ⋅ 4 = 6 \left(\begin{matrix}

-2 \\ 0 \\ 2

\end{matrix}\right)

\circ

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ 2 \\ 4

\end{matrix}\right)

=

-2 \cdot 1 + 0 \cdot 2 + 2 \cdot 4 = 6 − 2 0 2 ∘ 1 2 4 = − 2 ⋅ 1 + 0 ⋅ 2 + 2 ⋅ 4 = 6 ( 1 − 2 − 1 ) ∘ ( 3 1 1 ) = 1 ⋅ 3 + ( − 2 ) ⋅ 1 + ( − 1 ) ⋅ 1 = 0 \left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ -2 \\ -1

\end{matrix}\right)

\circ

\left(\begin{matrix}

3 \\ 1 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

=

1 \cdot 3 + (-2) \cdot 1 + (-1) \cdot 1 = 0 1 − 2 − 1 ∘ 3 1 1 = 1 ⋅ 3 + ( − 2 ) ⋅ 1 + ( − 1 ) ⋅ 1 = 0 Kreuzprodukt 💡

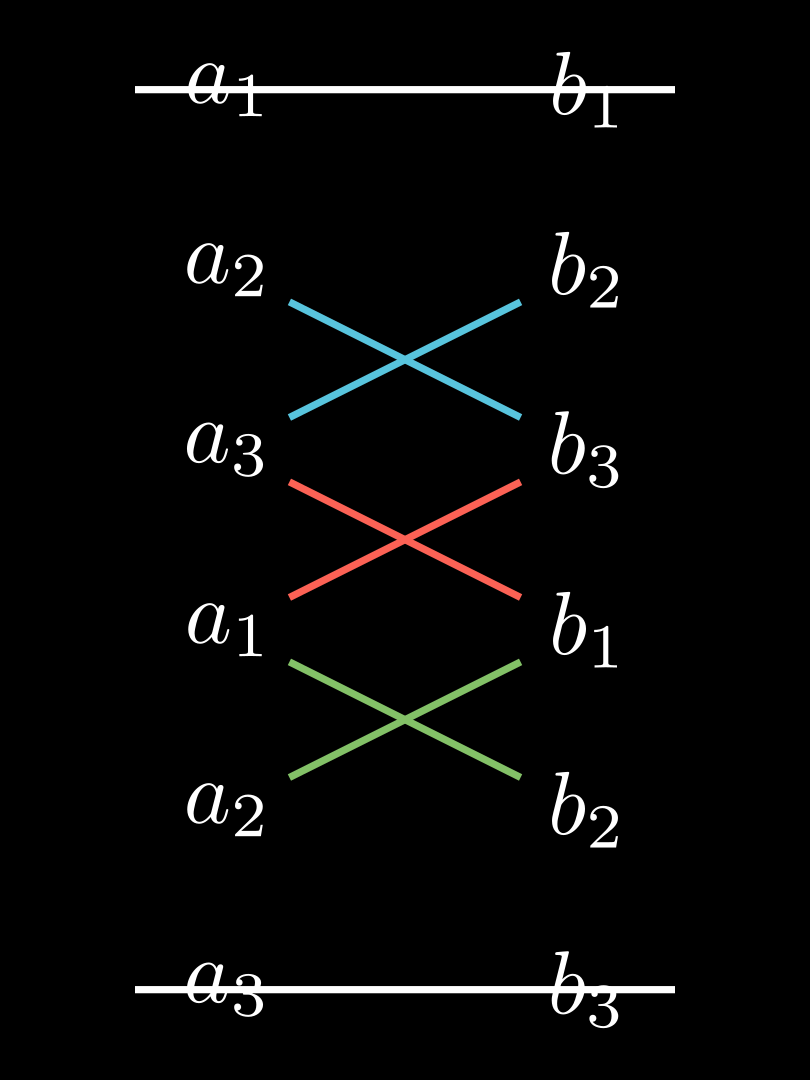

Das Kreuzprodukt zwischen a ⃗ = ( a 1 a 2 a 3 ) \vec a = \left(\begin{smallmatrix}

a_1\\a_2\\a_3

\end{smallmatrix}\right) a = ( a 1 a 2 a 3 ) b ⃗ = ( b 1 b 2 b 3 ) \vec b = \left(\begin{smallmatrix}

b_1\\b_2\\b_3

\end{smallmatrix}\right) b = ( b 1 b 2 b 3 )

a ⃗ × b ⃗ = ( a 2 b 3 − a 3 b 2 a 3 b 1 − a 1 b 3 a 1 b 2 − a 2 b 1 ) \vec a \times \vec b =

\left(\begin{matrix}

\color{#58C4DD}a_2b_3 - a_3b_2 \\

\color{#FC6255}a_3b_1 - a_1b_3 \\

\color{#83C167}a_1b_2 - a_2b_1

\end{matrix}\right) a × b = a 2 b 3 − a 3 b 2 a 3 b 1 − a 1 b 3 a 1 b 2 − a 2 b 1 Eselsbrücke (siehe Diagramm):

Man schreibt die Vektoren zweimal untereinander. Streicht die erste und letzte Zeile weg. Multipliziert die verbleibenden Werte über Kreuz und bilde die Differenz der Produkte. Satz 💡

Der resultierende Vektor aus a ⃗ × b ⃗ \vec a \times \vec b a × b senkrecht auf a ⃗ \vec a a b ⃗ \vec b b a ⃗ \vec a a b ⃗ \vec b b

Beispiele ( 3 − 5 1 ) × ( − 2 0 4 ) = ( − 5 ⋅ 4 − 1 ⋅ 0 1 ⋅ ( − 2 ) − 3 ⋅ 4 3 ⋅ 0 − ( − 5 ) ⋅ − 2 ) = ( − 20 − 14 − 10 ) \left(\begin{matrix}

3 \\ -5 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

\times

\left(\begin{matrix}

-2 \\ 0 \\ 4

\end{matrix}\right)

=

\left(\begin{matrix}

-5 \cdot 4 - 1 \cdot 0\\

1 \cdot (-2) - 3 \cdot 4 \\

3 \cdot 0 - (-5) \cdot -2

\end{matrix}\right)

=

\left(\begin{matrix}

-20 \\ -14 \\ -10

\end{matrix}\right) 3 − 5 1 × − 2 0 4 = − 5 ⋅ 4 − 1 ⋅ 0 1 ⋅ ( − 2 ) − 3 ⋅ 4 3 ⋅ 0 − ( − 5 ) ⋅ − 2 = − 20 − 14 − 10 ( 2 4 − 1 ) × ( 1 − 3 2 ) = ( 4 ⋅ 2 − ( − 1 ) ⋅ ( − 3 ) ( − 1 ) ⋅ 1 − 2 ⋅ 2 2 ⋅ ( − 3 ) − 4 ⋅ 1 ) = ( 5 − 5 − 10 ) \left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ 4 \\ -1

\end{matrix}\right)

\times

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ -3 \\ 2

\end{matrix}\right)

=

\left(\begin{matrix}

4 \cdot 2 - (-1) \cdot (-3) \\

(-1) \cdot 1 - 2 \cdot 2 \\

2 \cdot (-3) - 4 \cdot 1\end{matrix}\right)

=

\left(\begin{matrix}

5 \\ -5 \\ -10

\end{matrix}\right) 2 4 − 1 × 1 − 3 2 = 4 ⋅ 2 − ( − 1 ) ⋅ ( − 3 ) ( − 1 ) ⋅ 1 − 2 ⋅ 2 2 ⋅ ( − 3 ) − 4 ⋅ 1 = 5 − 5 − 10 Geradengleichung 💡

Gegeben sind ein Punkt P P P p ⃗ \vec p p u ⃗ ≠ o ⃗ \vec u \neq \vec o u = o P P P u ⃗ \vec u u

g : x ⃗ = p ⃗ + t ⋅ u ⃗ , t ∈ R g: \vec x =

\vec p + t \cdot \vec u, \ t \in \R g : x = p + t ⋅ u , t ∈ R x ⃗ \vec x x g g g p ⃗ \vec p p Stützvektor u ⃗ \vec u u Richtungsvektor t t t Parameter

Gerade durch zwei Punkte aufstellen A = ( 1 ∣ 2 ∣ 1 ) B = ( 3 ∣ 5 ∣ 5 ) A = (1 \, | \, 2 \, | \, 1) \qquad

B = (3 \, | \, 5 \, | \, 5) A = ( 1 ∣ 2 ∣ 1 ) B = ( 3 ∣ 5 ∣ 5 ) g : x ⃗ = O A → + t ⋅ A B → = ( 1 2 1 ) + t ⋅ ( 2 3 4 ) g: \vec x =

\overrightarrow{OA} + t\cdot

\overrightarrow{AB}

=

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ 2 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

+ t \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ 3 \\ 4

\end{matrix}\right) g : x = O A + t ⋅ A B = 1 2 1 + t ⋅ 2 3 4 Punktprobe Liegt P P P g g g

P ( 3 ∣ 8 ∣ − 3 ) g : x ⃗ = ( 1 2 1 ) + t ⋅ ( 2 3 4 ) P(3 \, | \, 8 \, | -3)

\qquad

g: \vec x =

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ 2 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

+ t \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ 3 \\ 4

\end{matrix}\right) P ( 3 ∣ 8 ∣ − 3 ) g : x = 1 2 1 + t ⋅ 2 3 4 ( 3 8 − 3 ) = ( 1 2 1 ) + t ⋅ ( 2 3 4 ) ∣ − ( 1 2 1 ) ( 2 6 − 4 ) = t ⋅ ( 2 3 4 ) ⇒ t = 1 ⇒ t = 2 ⇒ t = − 1 ⇒ P liegt nicht auf g \begin{align*}

\left(\begin{matrix}

3 \\ 8 \\ -3

\end{matrix}\right)

&=

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ 2 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

+ t \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ 3 \\ 4

\end{matrix}\right)

\quad \left|-

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ 2 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)\right.

\\

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ 6 \\ -4

\end{matrix}\right)

&=

t \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ 3 \\ 4

\end{matrix}\right)

\begin{align*}

\Rightarrow t &= 1\\

\Rightarrow t &= 2\\

\Rightarrow t &= -1

\end{align*}

\end{align*}

\\

\boxed{

\Rightarrow P \text{ liegt nicht auf }g

} 3 8 − 3 2 6 − 4 = 1 2 1 + t ⋅ 2 3 4 − 1 2 1 = t ⋅ 2 3 4 ⇒ t ⇒ t ⇒ t = 1 = 2 = − 1 ⇒ P liegt nicht auf g Ebenengleichung: Parametergleichung 💡

Gegeben ist ein Stützvektor p ⃗ \vec p p u ⃗ \vec u u v ⃗ \vec v v Parameterform oder Parametergleichung der Ebene E E E

E : x ⃗ + r ⋅ u ⃗ + s ⋅ v ⃗ r , s ∈ R , u ⃗ ≠ o ⃗ ≠ v ⃗ E: \vec x +

r \cdot \vec u +

s \cdot \vec v

\\

r,s \in \R,

\vec u \neq \vec o \neq \vec v E : x + r ⋅ u + s ⋅ v r , s ∈ R , u = o = v Ebene durch drei Punkte aufstellen A ( 1 ∣ − 1 ∣ 1 ) B ( 1 , 5 ∣ 1 ∣ 0 ) C ( 0 ∣ 1 ∣ 1 ) A(1 \, | -1 \, | \, 1) \qquad

B(1{,}5 \, | \, 1 \, | \ 0) \qquad

C(0 \, | \, 1 \, | \, 1) A ( 1 ∣ − 1 ∣ 1 ) B ( 1 , 5 ∣ 1 ∣ 0 ) C ( 0 ∣ 1 ∣ 1 ) E : x ⃗ = ( 1 − 1 1 ) ⏟ O A → + r ⋅ ( 0 , 5 2 − 1 ) ⏟ A B → + s ⋅ ( − 1 2 0 ) ⏟ A C → E: \vec x =

\underbrace{

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ -1 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

}_{\overrightarrow{OA}}

+ r \cdot

\underbrace{

\left(\begin{matrix}

0{,}5 \\ 2 \\ -1

\end{matrix}\right)

}_{\overrightarrow{AB}}

+ s \cdot

\underbrace{

\left(\begin{matrix}

-1 \\ 2 \\ 0

\end{matrix}\right)

}_{\overrightarrow{AC}} E : x = O A 1 − 1 1 + r ⋅ A B 0 , 5 2 − 1 + s ⋅ A C − 1 2 0 Punktprobe Liegt P P P E E E

P ( 5 ∣ 3 ∣ − 5 ) E : x ⃗ = ( 1 − 1 1 ) + r ⋅ ( 0 , 5 2 − 1 ) + s ⋅ ( − 1 2 0 ) P(5 \, | \, 3 \, | -5)

\qquad

E: \vec x =

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ -1 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

+ r \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

0{,}5 \\ 2 \\ -1

\end{matrix}\right)

+ s \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

-1 \\ 2 \\ 0

\end{matrix}\right) P ( 5 ∣ 3 ∣ − 5 ) E : x = 1 − 1 1 + r ⋅ 0 , 5 2 − 1 + s ⋅ − 1 2 0 ( 5 3 − 5 ) = ( 1 − 1 1 ) + r ⋅ ( 0 , 5 2 − 1 ) + s ⋅ ( − 1 2 0 ) ∣ − ( 1 − 1 1 ) ( 4 4 − 6 ) = r ⋅ ( 0 , 5 2 − 1 ) + s ⋅ ( − 1 2 0 ) \begin{align*}

\left(\begin{matrix}

5 \\ 3 \\ -5

\end{matrix}\right)

&=

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ -1 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

+ r \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

0{,}5 \\ 2 \\ -1

\end{matrix}\right)

+ s \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

-1 \\ 2 \\ 0

\end{matrix}\right)

\quad\left |-

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ -1 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

\right.

\\

\left(\begin{matrix}

4 \\ 4 \\ -6

\end{matrix}\right)

&=

r \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

0{,}5 \\ 2 \\ -1

\end{matrix}\right)

+ s \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

-1 \\ 2 \\ 0

\end{matrix}\right)

\end{align*} 5 3 − 5 4 4 − 6 = 1 − 1 1 + r ⋅ 0 , 5 2 − 1 + s ⋅ − 1 2 0 − 1 − 1 1 = r ⋅ 0 , 5 2 − 1 + s ⋅ − 1 2 0 ⇒ ( 0 , 5 − 1 4 2 2 4 − 1 0 − 6 ) ⇒ s = − 1 ⇒ s = − 4 ⇒ r = 6 ⇒ P liegt nicht auf E \Rightarrow

\left(

\begin{array}{cc|c}

0{,}5 & -1 & 4 \\

2 & 2 & 4 \\

-1 & 0 & -6

\end{array}

\right)

\begin{align*}

\Rightarrow s &= -1 \\

\Rightarrow s &= -4 \\

\Rightarrow r &= 6

\end{align*}

\\

\boxed{

\Rightarrow P \text{ liegt nicht auf } E

} ⇒ 0 , 5 2 − 1 − 1 2 0 4 4 − 6 ⇒ s ⇒ s ⇒ r = − 1 = − 4 = 6 ⇒ P liegt nicht auf E Ebenengleichung: Normalengleichung 💡

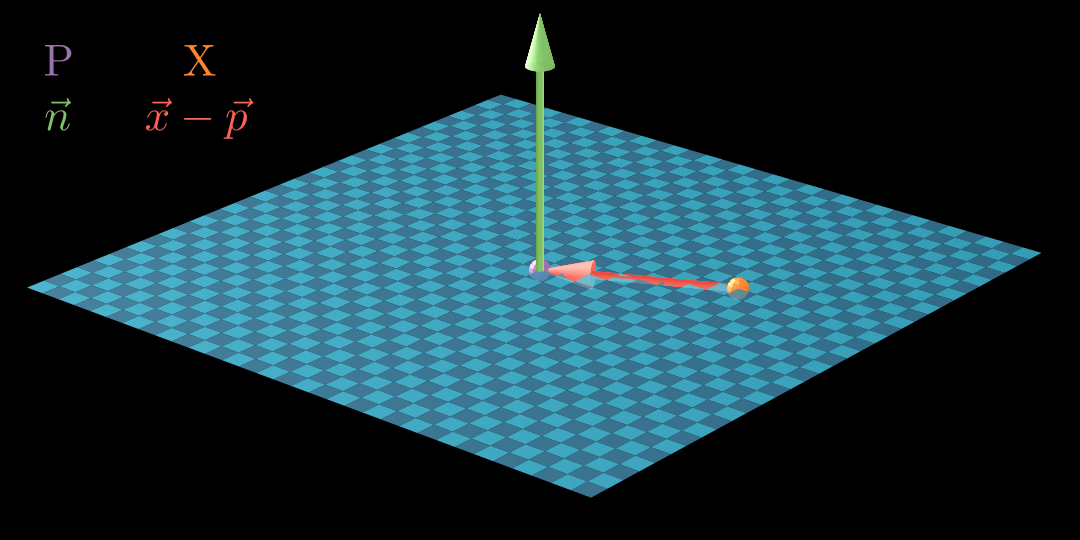

Jede Ebene E E E Normalenvektor n ⃗ \vec n n p ⃗ \vec p p

E : ( x ⃗ − p ⃗ ) ∘ n ⃗ = 0 E:

(\vec x - \vec p)

\circ \vec n = 0 E : ( x − p ) ∘ n = 0 Ebene aufstellen P ( 4 ∣ 1 ∣ 3 ) n ⃗ = ( 2 − 1 5 ) ⇒ E : [ x ⃗ − ( 4 1 3 ) ] ∘ ( 2 − 1 5 ) = 0 P(4 \, | \, 1 \, | \, 3) \qquad

\vec n =

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ -1 \\ 5

\end{matrix}\right)

\\

\Rightarrow

E:

\left[

\vec x -

\left(\begin{matrix}

4 \\ 1 \\ 3

\end{matrix}\right)

\right]

\circ

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ -1 \\ 5

\end{matrix}\right)

= 0 P ( 4 ∣ 1 ∣ 3 ) n = 2 − 1 5 ⇒ E : x − 4 1 3 ∘ 2 − 1 5 = 0 Punktprobe Liegt Q Q Q E E E

Q ( 2 ∣ 1 ∣ 4 ) E : [ x ⃗ − ( 4 1 3 ) ] ∘ ( 2 − 1 5 ) = 0 Q(2 \, | \, 1 \, | \, 4)

\qquad

E:

\left[

\vec x -

\left(\begin{matrix}

4 \\ 1 \\ 3

\end{matrix}\right)

\right]

\circ

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ -1 \\ 5

\end{matrix}\right)

= 0 Q ( 2 ∣ 1 ∣ 4 ) E : x − 4 1 3 ∘ 2 − 1 5 = 0 [ ( 2 1 4 ) − ( 4 1 3 ) ] ∘ ( 2 − 1 5 ) = ? 0 ( − 2 0 1 ) ∘ ( 2 − 1 5 ) = 0 − 2 ⋅ 2 + 0 ⋅ ( − 1 ) + 1 ⋅ 5 = 0 1 ≠ 0 ⇒ P liegt nicht auf E \begin{align*}

\left[

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ 1 \\ 4

\end{matrix}\right)

-

\left(\begin{matrix}

4 \\ 1 \\ 3

\end{matrix}\right)

\right]

\circ

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ -1 \\ 5

\end{matrix}\right)

&\stackrel{?}{=} 0

\\

\left(\begin{matrix}

-2 \\ 0 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

\circ

\left(\begin{matrix}

2 \\ -1 \\ 5

\end{matrix}\right)

&= 0

\\

-2 \cdot 2 +

0 \cdot (-1) +

1 \cdot 5

&= 0

\\

1 &\neq 0

\end{align*}

\\

\boxed{

\Rightarrow P \text{ liegt nicht auf } E

} 2 1 4 − 4 1 3 ∘ 2 − 1 5 − 2 0 1 ∘ 2 − 1 5 − 2 ⋅ 2 + 0 ⋅ ( − 1 ) + 1 ⋅ 5 1 = ? 0 = 0 = 0 = 0 ⇒ P liegt nicht auf E Ebenengleichung: Koordinatengleichung 💡

Jede Ebene E E E Koordinatengleichung beschrieben werden:

E : a x 1 + b x 2 + c x 3 = d E: ax_1 + bx_2 + cx_3 = d E : a x 1 + b x 2 + c x 3 = d Dabei ist ( a b c ) \left(\begin{smallmatrix}

a \\ b \\ c

\end{smallmatrix}\right) ( a b c ) E E E

Ebene durch drei Punkten aufstellen A ( 5 ∣ − 2 ∣ 4 ) B ( − 3 ∣ 0 ∣ 1 ) C ( 3 ∣ 4 ∣ 2 ) A(5 \, | -2 \, | \, 4) \quad

B(-3 \, | \ 0 \, | \, 1) \quad

C(3 \, | \ 4 \, | \, 2) A ( 5 ∣ − 2 ∣ 4 ) B ( − 3 ∣ 0 ∣ 1 ) C ( 3 ∣ 4 ∣ 2 ) A B → = ( − 8 2 − 3 ) A C → = ( − 2 4 − 2 ) A B → × A C → = ( − 8 2 − 3 ) × ( − 2 4 − 2 ) = ( 8 − 10 − 28 ) ⇒ n ⃗ = ( 4 − 5 − 14 ) \overrightarrow{AB} = \left(\begin{matrix}

-8 \\ 2 \\ -3

\end{matrix}\right)

\qquad

\overrightarrow{AC} = \left(\begin{matrix}

-2 \\ 4 \\ -2

\end{matrix}\right)

\\

\overrightarrow{AB} \times \overrightarrow{AC} =

\left(\begin{matrix}

-8 \\ 2 \\ -3

\end{matrix}\right)

\times

\left(\begin{matrix}

-2 \\ 4 \\ -2

\end{matrix}\right)

=

\left(\begin{matrix}

8 \\ -10 \\ -28

\end{matrix}\right)

\quad\Rightarrow

\vec n =

\left(\begin{matrix}

4 \\ -5 \\ -14

\end{matrix}\right) A B = − 8 2 − 3 A C = − 2 4 − 2 A B × A C = − 8 2 − 3 × − 2 4 − 2 = 8 − 10 − 28 ⇒ n = 4 − 5 − 14 ❗

Probe machen: n ⃗ ∘ A B → = 0 \color{df5441}\vec n \circ \overrightarrow{AB} = 0 n ∘ A B = 0 und n ⃗ ∘ A C → = 0 \color{df5441}\vec n \circ \overrightarrow{AC} = 0 n ∘ A C = 0 .

E : 4 x 1 − 5 x 2 − 14 x 3 = − 26 ⏟ NR (B eingesetzt): 4 ⋅ ( − 3 ) − 5 ⋅ 0 − 14 ⋅ 1 = − 26 E: 4x_1-5x_2-14x_3=

\underbrace{-26}

\\

\text{NR (B eingesetzt): }

4 \cdot (-3) -

5 \cdot 0 -

14 \cdot 1 = -26 E : 4 x 1 − 5 x 2 − 14 x 3 = − 26 NR (B eingesetzt): 4 ⋅ ( − 3 ) − 5 ⋅ 0 − 14 ⋅ 1 = − 26 Punktprobe Liegt P P P E E E

P ( 3 ∣ 2 ∣ 2 ) E : 4 x 1 − 5 x 2 − 14 x 3 = − 26 P(3 \ | \ 2 \ | \ 2) \quad

E: 4x_1 - 5x_2 - 14x_3 = -26 P ( 3 ∣ 2 ∣ 2 ) E : 4 x 1 − 5 x 2 − 14 x 3 = − 26 4 ⋅ 3 − 5 ⋅ 2 − 14 ⋅ 2 = ? − 26 − 26 = − 26 ⇒ P liegt auf E \begin{align*}

4 \cdot 3 -

5 \cdot 2 -

14 \cdot 2

&\stackrel{?}{=} -26

\\

-26 &= -26

\end{align*}

\\

\boxed{

\Rightarrow P \text{ liegt auf }E

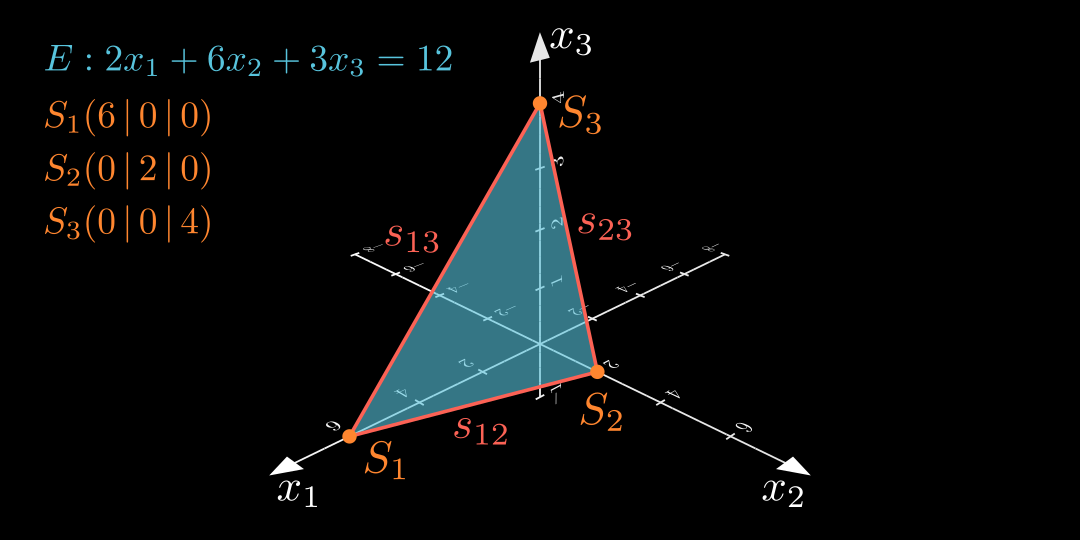

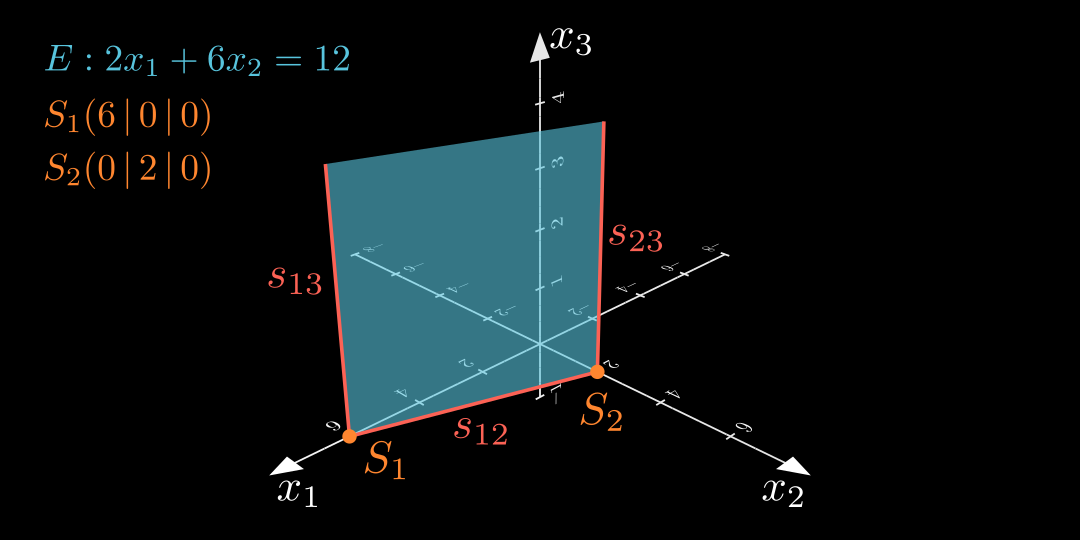

} 4 ⋅ 3 − 5 ⋅ 2 − 14 ⋅ 2 − 26 = ? − 26 = − 26 ⇒ P liegt auf E Spurpunkte und Spurgeraden 💡

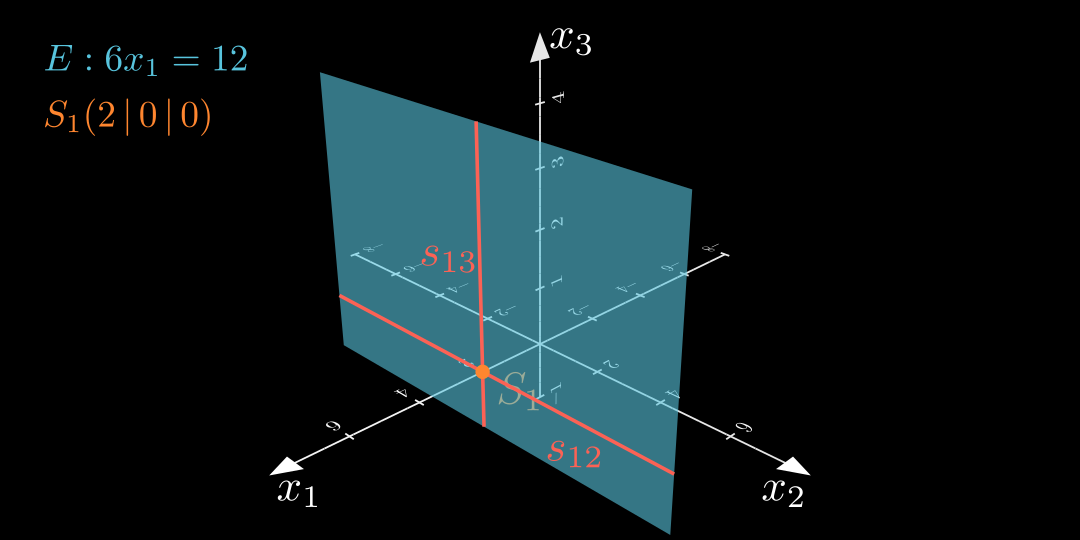

Um eine Ebene in einem Koordinatensystem zu veranschaulichen, zeichnet man einen Ausschnitt der Ebene. Dabei orientiert man sich an den jeweiligen Schnittpunkten der Ebene mit den Koordinatenachsen. Diese Punkte heißen Spurpunkte .

💡

Die Gesamtheit aller Schnittpunkte einer Ebene mit einer Koordinatenebene heißen Spurgerade .

In den folgenden Beispielen sind stets alle Spurpunkte \color{#FF862F} \text{Spurpunkte} Spurpunkte Spurgeraden \color{#FC6255}\text{Spurgeraden} Spurgeraden

Achsenabschnittsform 💡

Wenn man alle Spurpunkte einer Ebene kennt, die nicht durch den Ursprung verläuft, so kann man direkt deren Achsenabschnittsform (eine spezielle Koordinatengleichung) anlegen.

Beispiel S 1 ( 5 ∣ 0 ∣ 0 ) S 2 ( 0 ∣ − 2 ∣ 0 ) S 3 ( 0 ∣ 0 ∣ 0 , 5 ) S_1 (5 \, | \, 0 \, | \, 0) \quad

S_2 (0 \, | -2 \, | \, 0) \quad

S_3 (0 \, | \, 0 \, | \, 0{,}5) S 1 ( 5 ∣ 0 ∣ 0 ) S 2 ( 0 ∣ − 2 ∣ 0 ) S 3 ( 0 ∣ 0 ∣ 0 , 5 ) ⇒ E : 1 5 x 1 − 1 2 x 2 + 2 x 3 = 1 ∣ ⋅ 10 E : 2 x 1 − 5 x 2 + 20 x 3 = 10 \begin{align*}

\Rightarrow

E: \frac 15 x_1 -

\frac12 x_2 + 2x_3 &= 1

\quad | \cdot 10

\\

E: 2x_1 - 5x_2 + 20x_3 &= 10

\end{align*} ⇒ E : 5 1 x 1 − 2 1 x 2 + 2 x 3 E : 2 x 1 − 5 x 2 + 20 x 3 = 1 ∣ ⋅ 10 = 10 Gegenseitige Lage von Ebenen und Geraden 💡

Wenn der Normalenvektor der Ebene ein Vielfaches des Richtungsvektors ist, so schneidet die Gerade die Ebene orthogonal. Wenn das Skalarprodukt von Normalenvektor der Ebene und Richtungsvektor der Geraden 0 ist, so ist die Gerade in der Ebene enthalten, wenn der Stützvektor in der Ebene enthalten ist. Ist der Stützvektor nicht in der Ebene enthalten, so ist die Gerade parallel zur Ebene. Ansonsten und in Fall 1 gibt es genau einen Schnittpunkt (Durchstoßpunkt ). Durchstoßpunkt berechnen E : x 1 − x 2 + 2 x 3 = 9 g : x ⃗ = ( 3 2 0 ) + t ⋅ ( − 2 2 3 ) E: x_1 -x_2 + 2x_3 = 9 \qquad

g: \vec x =

\left(\begin{matrix}

3 \\ 2 \\ 0

\end{matrix}\right)

+

t \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

-2 \\ 2 \\ 3

\end{matrix}\right)

\qquad E : x 1 − x 2 + 2 x 3 = 9 g : x = 3 2 0 + t ⋅ − 2 2 3 Schneide E & g ( g in E einsetzen): ( 3 − 2 t ) − ( 2 + 2 t ) + 2 ⋅ ( 0 + 3 t ) = 9 1 + 2 t = 9 ∣ − 1 ∣ : 2 t = 4 t = 4 in g einsetzen: ⇒ S ( − 5 ∣ 10 ∣ 12 ) \text{Schneide } E \text{ \& } g

\text{ (} g \text{ in } E \text{ einsetzen): }

\\

\begin{align*}

(3-2t) - (2+2t) +

2 \cdot (0 + 3t) &= 9

\\

1 + 2t &= 9

\quad

| -1 \quad |:2

\\

t &= 4

\end{align*}

\\

t=4 \text{ in } g \text{ einsetzen:}

\\

\boxed{

\Rightarrow

S(-5 \, | \, 10 \, | 12)

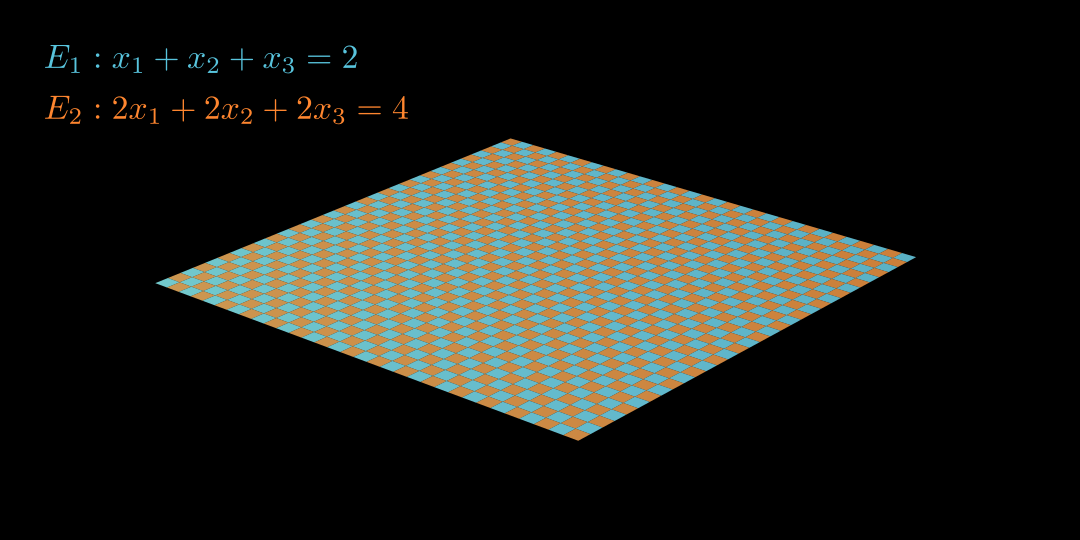

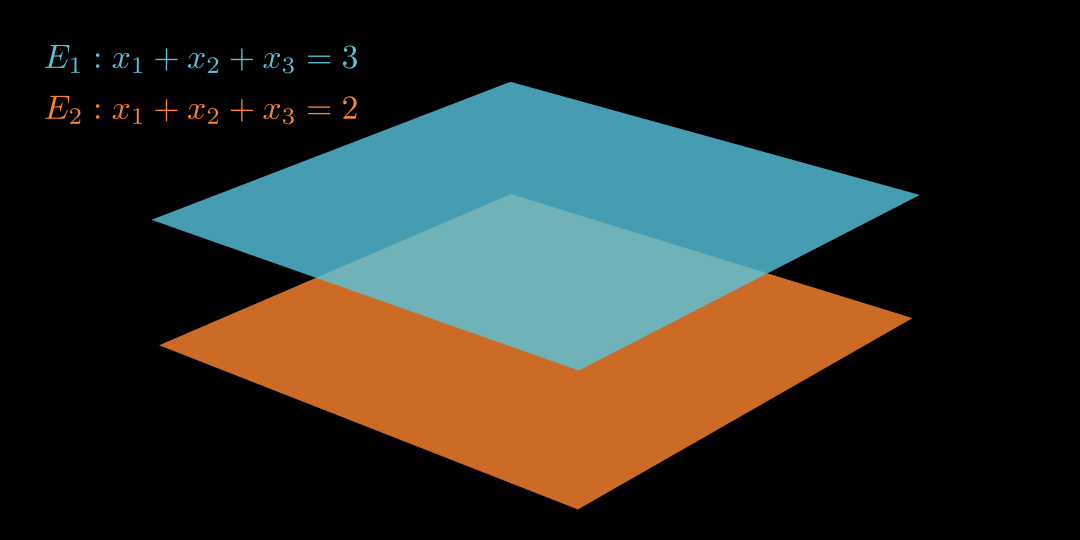

} Schneide E & g ( g in E einsetzen): ( 3 − 2 t ) − ( 2 + 2 t ) + 2 ⋅ ( 0 + 3 t ) 1 + 2 t t = 9 = 9 ∣ − 1 ∣ : 2 = 4 t = 4 in g einsetzen: ⇒ S ( − 5 ∣ 10 ∣12 ) Gegenseitige Lage von Ebenen Identisch Normalenvektoren und Koordinatengleichungen sind Vielfache voneinander.

Parallel Normalenvektoren sind Vielfache voneinander, aber Koordinatengleichungen sind keine vielfache voneinander.

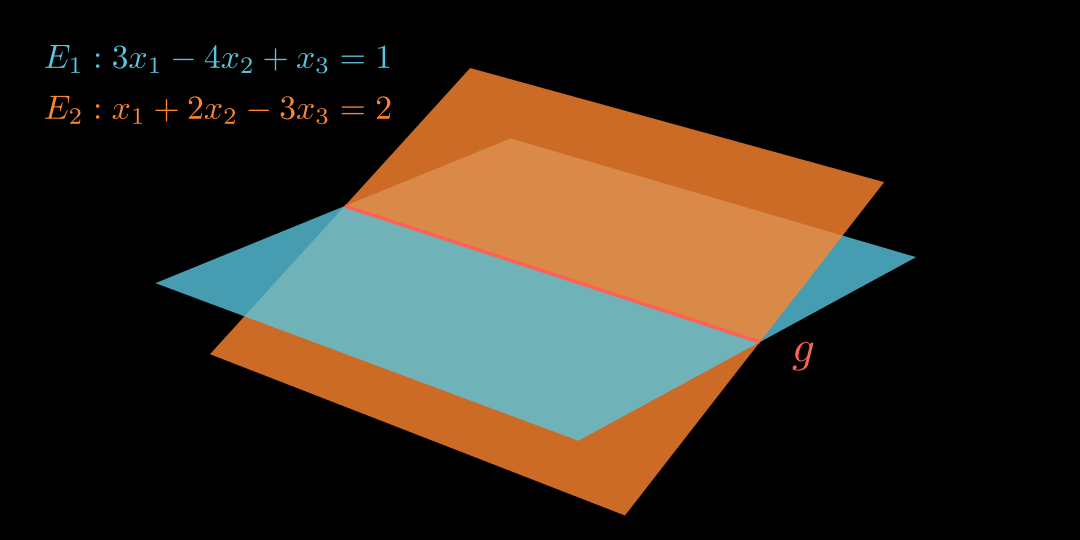

Schneidend Schnittgerade bestimmen E 1 : 3 x 1 − 4 x 2 + x 3 = 1 E 2 : x 1 + 2 x 2 − 3 x 3 = 2 E_1: 3x_1 - 4x_2 + x_3 = 1 \\

E_2: x_1 + 2x_2 - 3x_3 = 2 E 1 : 3 x 1 − 4 x 2 + x 3 = 1 E 2 : x 1 + 2 x 2 − 3 x 3 = 2 Unterbestimmtes LGS: I) II) I − 3 I I ) 3 x 1 − 4 x 2 + x 3 = 1 x 1 + 2 x 2 − 3 x 3 = 2 x 1 − 10 x 2 + 10 x 3 = 5 \text{Unterbestimmtes LGS:}

\\

\begin{align*}

\textit{I) } \ \\

\textit{II) } \ \\

\textit{I } -3 {II) } \

\end{align*}

\begin{alignat*} {5}

3 &x_1 - &4 &x_2 + &&x_3 = 1 \\

&x_1 + &2 &x_2 - & 3 &x_3 = 2 \\

&\phantom{x_1} - &10 &x_2 + &10 &x_3 = 5

\end{alignat*} Unterbestimmtes LGS: I) II) I − 3 II ) 3 x 1 − x 1 + x 1 − 4 2 10 x 2 + x 2 − x 2 + 3 10 x 3 = 1 x 3 = 2 x 3 = 5 W a ¨ hle x 3 = t : ⇒ x 2 = − 1 2 + t ⇒ x 1 = 3 + t ⇒ g : x ⃗ = ( 3 − 1 2 0 ) + t ⋅ ( 1 1 1 ) \text{Wähle } x_3 = t:

\quad

\begin{align*}

\Rightarrow x_2 &= -\frac12 + t\\

\Rightarrow x_1 &= 3 + t

\end{align*}

\\

\boxed{

\Rightarrow g: \vec x =

\left(\begin{matrix}

3 \\ -\frac12 \\ 0

\end{matrix}\right)

+

t \cdot

\left(\begin{matrix}

1 \\ 1 \\ 1

\end{matrix}\right)

} W a ¨ hle x 3 = t : ⇒ x 2 ⇒ x 1 = − 2 1 + t = 3 + t ⇒ g : x = 3 − 2 1 0 + t ⋅ 1 1 1

🔎