🔎

💬

Ich nehme an, dass man lineare und quadratische Gleichungen (mit der abc-/Mitternachts- oder pq-Formel) lösen kann.

Lösungsmenge Die Lösungsmenge L L L

Beispiele x + 4 = 7 ⇒ L = { 3 } x 2 = 4 ⇒ L = { − 2 ; 2 } x + 3 > 8 ⇒ L = ] 5 ; ∞ [ sin ( x ) = 1 ⇒ L = { x ∈ R ∣ x = 1 2 π + k ⋅ 2 π , k ∈ Z } \begin{align}

x+4 &= 7

\quad&\Rightarrow\quad

L &= \{3\} \\

x^2 &= 4

\quad&\Rightarrow\quad

L &= \{-2; 2\} \\

x+3 &> 8

\quad&\Rightarrow\quad

L &= \ ]5; \infty[ \\

\sin(x) &= 1

\quad&\Rightarrow\quad

L &=

\{x \in \mathbb R \ | \

x = \frac12 \pi+k \cdot 2\pi,\

k \in \mathbb Z

\}

\end{align} x + 4 x 2 x + 3 sin ( x ) = 7 = 4 > 8 = 1 ⇒ L ⇒ L ⇒ L ⇒ L = { 3 } = { − 2 ; 2 } = ] 5 ; ∞ [ = { x ∈ R ∣ x = 2 1 π + k ⋅ 2 π , k ∈ Z } Satz vom Nullprodukt 💡

Ein Produkt ist 0, wenn mindestens einer der Faktoren 0 ist.

Beispiel ( x − 5 ) ⋅ ( x 2 − x + 4 ) = 0 ⇒ I ) x − 5 = 0 I I ) x 2 − x + 4 = 0 ⇒ I ) x 1 = 5 I I ) keine L o ¨ sung \begin{equation*}

(x-5)\cdot(x^2-x+4)=0 \quad

\end{equation*}

\Rightarrow\quad

\begin{align*}

&\mathrm{I}) \hspace{3.5mm} x-5=0\\

&\mathrm{II}) \hspace{2mm} x^2-x+4=0

\end{align*}

\quad\Rightarrow\quad

\begin{align*}

\mathrm{I)}\ &x_1 = 5\\

\mathrm{II)}\ &\text{keine Lösung}

\end{align*} ( x − 5 ) ⋅ ( x 2 − x + 4 ) = 0 ⇒ I ) x − 5 = 0 II ) x 2 − x + 4 = 0 ⇒ I ) II ) x 1 = 5 keine L o ¨ sung (spezielle) kubische Gleichungen Beispiele x 3 + 27 = 0 x 3 = − 27 ⇒ x = − 27 3 \begin{align*}

x^3+27&=0\\

x^3&=-27\\

\Rightarrow x&=\mathbf{\color{red}-}\sqrt[3]{27}

\end{align*} x 3 + 27 x 3 ⇒ x = 0 = − 27 = − 3 27 4 x 3 − 12 x 2 − 40 x = 0 4 x ⋅ ( x 2 − 3 x − 10 ) = 0 ⇒ x 1 = 0 x 2 = 5 x 3 = − 2 \begin{align*}

4x^3-12x^2-40x&=0\\

4x\cdot (x^2-3x-10)&=0\\

\Rightarrow x_1=0 \quad x_2=5 \quad& x_3=-2

\end{align*} 4 x 3 − 12 x 2 − 40 x 4 x ⋅ ( x 2 − 3 x − 10 ) ⇒ x 1 = 0 x 2 = 5 = 0 = 0 x 3 = − 2 Nicht (analytisch) Lösbar x 3 − 7 x 2 + 5 = 0 x^3-7x^2+5=0 x 3 − 7 x 2 + 5 = 0 Biquadratische Gleichungen

Substitution

Rücksubstitution x 4 − 13 x 2 + 36 = 0 Substitution: x 2 = z ⇒ z 2 − 13 z + 36 = 0 ⇒ z 1 = 9 ; z 2 = 4 \begin{align*}

x^4-13x^2+36&=0\\

\textsf{Substitution: } x^2=z\\

\Rightarrow z^2-13z+36&=0\\

\Rightarrow z_1=9; z_2=4

\end{align*} x 4 − 13 x 2 + 36 Substitution: x 2 = z ⇒ z 2 − 13 z + 36 ⇒ z 1 = 9 ; z 2 = 4 = 0 = 0 x 2 = z 1 x 2 = 9 ∣ ⇒ x 1 = 3 x 2 = − 3 \begin{align*}

x^2&=z_1\\

x^2&=9 \quad |\sqrt{} \\

\Rightarrow \ &x_1=3\\

&x_2=-3

\end{align*} x 2 x 2 ⇒ = z 1 = 9 ∣ x 1 = 3 x 2 = − 3 x 2 = z 2 x 2 = 4 ∣ ⇒ x 3 = 2 x 4 = − 2 \begin{align*}

x^2&=z_2\\

x^2&=4 \quad |\sqrt{} \\

\Rightarrow \ &x_3=2\\

&x_4=-2

\end{align*} x 2 x 2 ⇒ = z 2 = 4 ∣ x 3 = 2 x 4 = − 2 Bruchgleichungen Beispiele x + 5 x − 3 − 3 = 0 ∣ ⋅ ( x − 3 ) 5 + x − 3 ⋅ ( x − 3 ) = 0 . . . x = 7 ✓ \begin{align*}

\frac{x+5}{x-3}-3&=0 \quad|\cdot(x-3)\\

5+x-3\cdot(x-3)&=0\\

&...\\

x&=7 \ \checkmark

\end{align*} x − 3 x + 5 − 3 5 + x − 3 ⋅ ( x − 3 ) x = 0 ∣ ⋅ ( x − 3 ) = 0 ... = 7 ✓ 1 x 2 + + 5 x = 0 ∣ ⋅ x 2 1 + 5 x = 0 ∣ − 1 ∣ : 5 x = − 1 5 ✓ \begin{align*}

\frac{1}{x^2}++\frac{5}{x}&=0

\qquad|\cdot x^2\\

1+5x&=0

\qquad|-1 \quad|:5\\

x&=-\frac{1}{5} \ \checkmark

\end{align*} x 2 1 + + x 5 1 + 5 x x = 0 ∣ ⋅ x 2 = 0 ∣ − 1 ∣ : 5 = − 5 1 ✓ ❗

Wurzelgleichungen Beispiel 3 x − 5 + 4 = 2 x ∣ − 4 ∣ 2 3 x − 5 = ( 2 x − 4 ) 2 . . . x 1 = 3 ✓ x 2 = 7 4 × \begin{align*}

\sqrt{3x-5} + 4 &= 2x

&|-4 \quad |^2\\

3x-5&=(2x-4)^2 \quad\\

&...\\

x_1 = 3 \ \checkmark&\quad x_2 = \frac{7}{4} \ \times

\end{align*} 3 x − 5 + 4 3 x − 5 x 1 = 3 ✓ = 2 x = ( 2 x − 4 ) 2 ... x 2 = 4 7 × ∣ − 4 ∣ 2 ❗

Exponentialgleichungen Allgemein a x = c x = log a ( c ) \begin{align*}

a^x&=c\\

x&=\log_a(c)\\

\end{align*} a x x = c = log a ( c ) b 0 = 1 , b ≠ 0 b^0 = 1, \quad b \neq 0 b 0 = 1 , b = 0 log e ( x ) = ln ( x ) \log_e(x) = \ln(x) log e ( x ) = ln ( x ) Beispiele 2 x = 64 x = log 2 ( 64 ) x = 6 \begin{align*}

2^x&=64\\

x&=\log_2(64)\\

x&=6

\end{align*} 2 x x x = 64 = log 2 ( 64 ) = 6 4 x = 42 x = log 4 ( 42 ) x ≈ 2.696 \begin{align*}

4^x&=42\\

x&=\log_4(42)\\

x&\approx2.696

\end{align*} 4 x x x = 42 = log 4 ( 42 ) ≈ 2.696 e 2 x − 3 e x = 0 ( e x ) 2 − 3 e x = 0 e x ⋅ ( e x − 3 ) = 0 ⇒ x = ln ( 3 ) \begin{align*}

e^{2x} - 3e^x &= 0 \\

(e^x)^2 - 3e^x &= 0 \\

e^x \cdot (e^x-3) &= 0 \\

\Rightarrow x &= \ln(3)

\end{align*} e 2 x − 3 e x ( e x ) 2 − 3 e x e x ⋅ ( e x − 3 ) ⇒ x = 0 = 0 = 0 = ln ( 3 ) Betragsgleichungen Beispiel ∣ 2 x − 5 ∣ = 3 ⇒ I ) 2 x − 5 = 3 I I ) 2 x − 5 = − 3 ⇒ I ) x 1 = 4 I I ) x 2 = 1 \begin{equation*}

|2x-5| = 3 \quad

\end{equation*}

\Rightarrow\quad

\begin{align*}

\mathrm{I)}\ 2x-5 &= 3 \\

\mathrm{II)}\ 2x-5 &= \mathbf{\color{red}-}3

\end{align*}

\quad\Rightarrow\quad

\begin{align*}

\mathrm{I)}\ x_1 &= 4\\

\mathrm{II)}\ x_2 &= 1

\end{align*} ∣2 x − 5∣ = 3 ⇒ I ) 2 x − 5 II ) 2 x − 5 = 3 = − 3 ⇒ I ) x 1 II ) x 2 = 4 = 1 ∣ x − 4 ∣ = 2 x − 11 ⇒ I ) x − 4 = 2 x − 11 I I ) x − 4 = − ( 2 x − 11 ) ⇒ I ) x 1 = 7 ✓ I I ) x 2 = 5 × \begin{equation*}

|x-4| = 2x-11 \quad

\end{equation*}

\Rightarrow\quad

\begin{align*}

\mathrm{I)}\ x-4 &= 2x-11 \\

\mathrm{II)}\ x-4 &= \mathbf{\color{red}-}(2x-11)

\end{align*}

\quad\Rightarrow\quad

\begin{align*}

\mathrm{I)}\ x_1 &= 7 \ \checkmark \\

\mathrm{II)}\ x_2 &= 5 \ \times

\end{align*} ∣ x − 4∣ = 2 x − 11 ⇒ I ) x − 4 II ) x − 4 = 2 x − 11 = − ( 2 x − 11 ) ⇒ I ) x 1 II ) x 2 = 7 ✓ = 5 × ❗

Bei Betragsgleichungen, die auch ein x x x außerhalb des Betrags beinhalten: Probe machen.

Ungleichungen Gleich zu lösen wie normale Gleichungen mit der Ausnahme, dass beim Multiplizieren mit einer negativen Zahl das Größer-/Kleiner-als-Zeichen umgekehrt wird.

Beispiele 2 x + 5 > 1 ∣ − 5 2 x > − 4 ∣ : 2 x > − 2 \begin{align*}

2x + 5 &> 1 \quad | -5 \\

2x &> -4 \quad |:2 \\

x &> -2

\end{align*} 2 x + 5 2 x x > 1 ∣ − 5 > − 4 ∣ : 2 > − 2 4 − x ≤ 8 ∣ − 4 − x ≤ 4 ∣ ⋅ ( − 1 ) x ≥ − 4 \begin{align*}

4 - x &\leq 8 \quad |-4 \\

-x &\leq 4 \quad

|{\color{red} \cdot (-1)} \\

x &\color{red}\geq \color{def}-4

\end{align*} 4 − x − x x ≤ 8 ∣ − 4 ≤ 4 ∣ ⋅ ( − 1 ) ≥ − 4 1 − ( 5 6 ) x > 0 , 9 ∣ − 1 − ( 5 6 ) x > − 0 , 1 ∣ ⋅ ( − 1 ) ( 5 6 ) x < 0 , 1 ∣ log 5 6 x > log 5 6 ( 0 , 1 ) ≈ 12 , 63 5 6 < 1 , deshalb ’<’ umdrehen \begin{alignat*} {3}

1-\left(\frac56\right)^x & > 0{,}9 \quad &|&-1 \\

-\left(\frac56\right)^x & > -0{,}1

\quad &|&\cdot (-1) \\

\left(\frac56\right)^x & < 0{,}1

\quad &| &\log_{\color{red}\frac56} \\

x &\color{red}>\color{default} \log_{\frac56}(0{,}1)&& \approx

12{,}63

\end{alignat*}

\\

\frac56 < 1, \text{deshalb '<' umdrehen} 1 − ( 6 5 ) x − ( 6 5 ) x ( 6 5 ) x x > 0 , 9 > − 0 , 1 < 0 , 1 > l o g 6 5 ( 0 , 1 ) ∣ ∣ ∣ − 1 ⋅ ( − 1 ) log 6 5 ≈ 12 , 63 6 5 < 1 , deshalb ’<’ umdrehen x 2 + x − 6 < 0 ⇒ x 2 + x − 6 = 0 ⇒ x 1 = − 3 x 2 = 2 Parabel nach oben ge o ¨ ffnet mit Nullstellen -3 und 2 ⇒ L = ] − 3 ; 2 [ x^2 +x - 6 < 0

\\

\Rightarrow x^2+x-6 = 0 \\

\Rightarrow x_1 = -3 \quad x_2 = 2 \\

\phantom{}\\\text{Parabel nach oben geöffnet }\\\text{mit Nullstellen -3 und 2}\\

\Rightarrow L = \ ]{-3}; 2[ x 2 + x − 6 < 0 ⇒ x 2 + x − 6 = 0 ⇒ x 1 = − 3 x 2 = 2 Parabel nach oben ge o ¨ ffnet mit Nullstellen -3 und 2 ⇒ L = ] − 3 ; 2 [ ∣ 32 − x ∣ < 10 ⇒ I ) 32 − x ≤ 10 I I ) − ( 32 − x ) ≤ 10 ⇒ I ) x ≥ 22 I I ) x ≤ 42 ⇒ L = [ 22 ; 42 ] |32-x| < 10

\quad\Rightarrow\quad

\begin{alignat*}{3}

\mathrm{I)}&\ &

32-x &\leq 10\\

\mathrm{II)}&\ &

-(32-x) &\leq 10

\end{alignat*}

\quad\Rightarrow\quad

\begin{align*}

\mathrm{I)}\ x \geq 22 \\

\mathrm{II)}\ x \leq 42

\end{align*}

\quad\Rightarrow\quad L=[22; 42] ∣32 − x ∣ < 10 ⇒ I ) II ) 32 − x − ( 32 − x ) ≤ 10 ≤ 10 ⇒ I ) x ≥ 22 II ) x ≤ 42 ⇒ L = [ 22 ; 42 ] 💬

Dass eine Gleichung wie im Beispiel in der Mitte rechts vorkommt, würde ich ausschließen. Das Lösen einer solchen Gleichung ist jedoch im Erwartungshorizont enthalten.

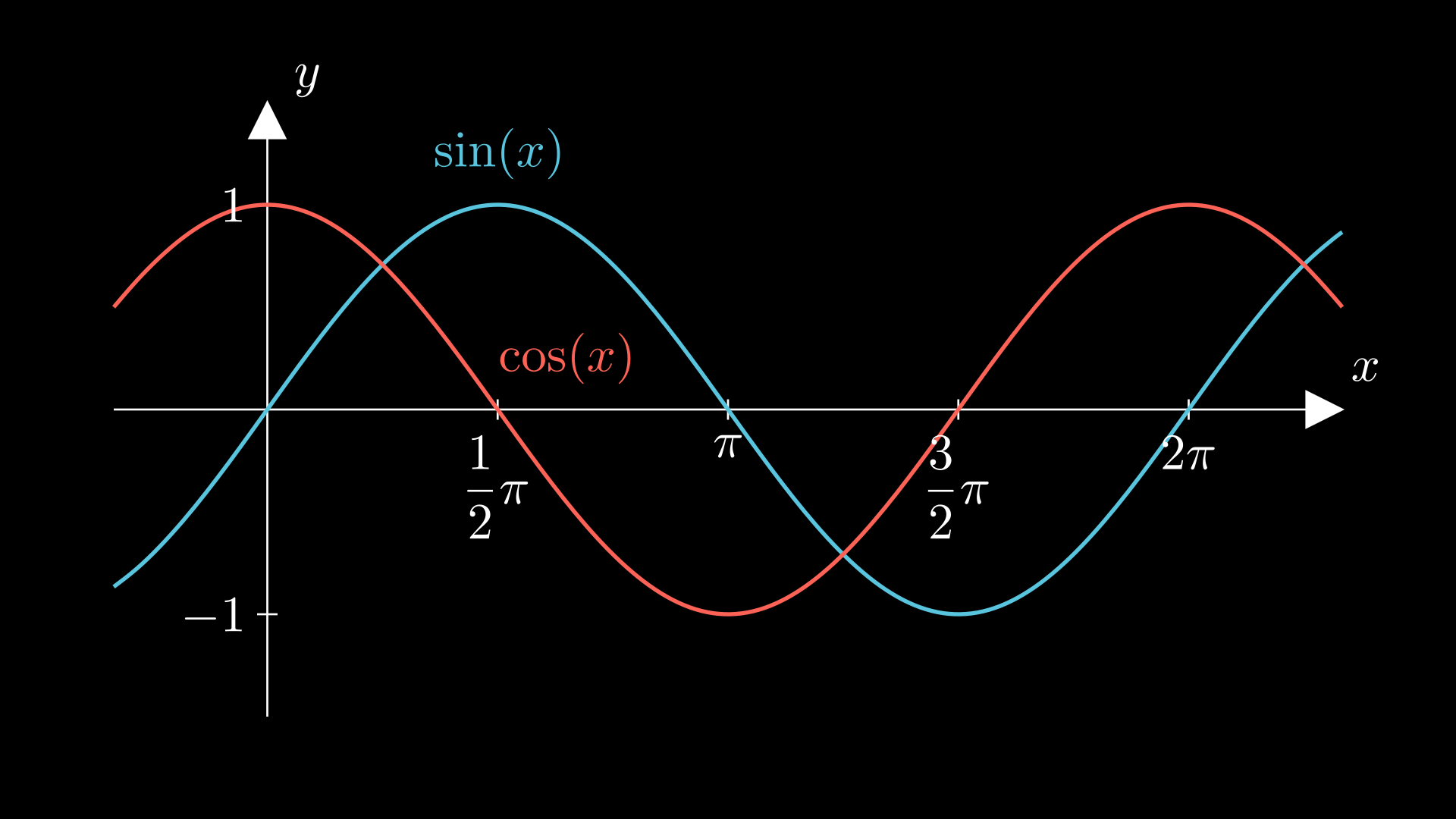

Trigonometrische Gleichungen Beispiele sin ( x ) + 2 = 1 , x ∈ [ 0 ; 2 π ] sin ( x ) = − 1 x = sin − 1 ( − 1 ) x = 3 2 π ⇒ L = { 3 2 π } \begin{align*}

\sin(x) + 2 &= 1\,,

\quad x \in [0; 2\pi]\\

\sin(x) &= -1\\

x &= \sin^{-1}(-1) \\

x &= \frac{3}{2}\pi \\

\Rightarrow L &= \{\frac{3}{2}\pi\}

\end{align*} sin ( x ) + 2 sin ( x ) x x ⇒ L = 1 , x ∈ [ 0 ; 2 π ] = − 1 = sin − 1 ( − 1 ) = 2 3 π = { 2 3 π } sin ( π x ) = − 1 , x ∈ R Substitution u = π x ⇒ sin ( u ) = − 1 ⇒ u = 3 2 π + k ⋅ 2 π , k ∈ Z R u ¨ cksubsstitution π x = 3 2 π + k ⋅ 2 π ∣ : π x = 3 2 + 2 k ⇒ L = { x ∈ R ∣ x = 3 2 + 2 k , k ∈ Z } ⇒ unendlich viele L o ¨ sungen ( 3 2 ; 7 2 ; − 1 2 , . . . ) \sin(\pi x) = -1\,,

\quad x \in \mathbb{R}\\

{}\\

\text{Substitution}\\

\begin{align*}

u &= \pi x\\

\Rightarrow \sin(u) &= -1\\

\Rightarrow u &= \frac{3}{2}\pi + k\cdot2\pi,

\quad k \in \mathbb{Z}\\

\end{align*}

\\

{}\\

\text{Rücksubsstitution}\\

\begin{align*}

\pi x &= \frac{3}{2}\pi + k\cdot2\pi

\quad | {: \pi}\\

x &= \frac{3}{2} + 2k

\end{align*}

\\

\Rightarrow L =

\{x \in \mathbb R \ | \

x = \frac32 + 2k,\

k \in \mathbb Z

\}\\

\\

\Rightarrow\textsf{unendlich viele Lösungen }(\frac32;\frac72;-\frac12,...) sin ( π x ) = − 1 , x ∈ R Substitution u ⇒ sin ( u ) ⇒ u = π x = − 1 = 2 3 π + k ⋅ 2 π , k ∈ Z R u ¨ cksubsstitution π x x = 2 3 π + k ⋅ 2 π ∣ : π = 2 3 + 2 k ⇒ L = { x ∈ R ∣ x = 2 3 + 2 k , k ∈ Z } ⇒ unendlich viele L o ¨ sungen ( 2 3 ; 2 7 ; − 2 1 , ... ) ⚠️

Bei Trigonometrischen Gleichungen auf den Definitionsbereich achten.

💬

Ich weiß, das zweite Beispiel kann erstmal überwältigend sein, aber versucht, es zu verstehen. Es wird wahrscheinlich eine Aufgabe mit so einer „komplizierten“ Lösungsmenge im Abi drankommen.

🔎